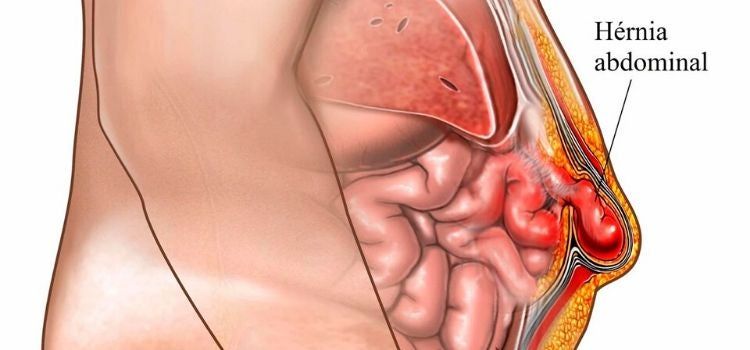

After abdominal surgery, the incision finally heals, but after a while, you may notice a bulge at the site of the surgery. This bulge is particularly noticeable when you stand, cough, or exert yourself. It retracts when you lie down or push gently with your hands, and sometimes there's a dull pain or pulling sensation. Doctors call this an incisional hernia. To put it simply, the supporting structure inside the abdomen (primarily the fascia layer) hasn't grown strong enough at the site of the surgical incision, leaving a weak spot or even a gap. The intestines or omentum inside squeeze out through this weak spot, forming a bulge under the skin. Don't underestimate it. Although it may only be a cosmetic issue or mild discomfort in the early stages, if left untreated, the bulge will grow larger, making you more uncomfortable and potentially causing your intestines to become stuck, incarcerated, or even necrotic and strangulated. This is a very dangerous emergency.

Why does the incision not grow firmly and cause an incisional hernia?

There are many reasons. First, your physical condition is crucial. If you have diabetes but poorly controlled blood sugar levels, or if you're not getting enough nutrition, especially protein, your body's repair capacity is weakened, making it difficult for the fascia to grow and strengthen. Obesity is also a significant factor. Abdominal fat creates increased tension, which, combined with the added pressure on the surgical incision, creates a significant burden on healing. For long-term smokers, nicotine can affect blood circulation, limiting blood flow to the wound and compromising healing quality. Second, the surgery itself and postoperative recovery can have a significant impact. For example, wound infection or subcutaneous fat liquefaction (a condition in which wounds leak and do not heal) can severely interfere with the proper healing of all layers of the incision, especially the crucial fascia. The location of the surgical incision is also crucial. Vertical incisions around the navel, mid-belly, or on the side of the abdomen near the waist are areas with inherently high tension and are more prone to problems. Poor suturing technique, inappropriate sutures, or premature detachment can also pose risks. Improper postoperative care is equally dangerous. For example, premature heavy work, strenuous activity, forceful coughing, straining to defecate due to constipation, or frequent sneezing can all increase abdominal pressure, repeatedly impacting the incision before it has healed properly, causing it to "stretch." Furthermore, if an emergency re-opening is necessary after surgery, repeated incisions and sutures can further complicate healing. Older patients, whose tissues are inherently more fragile and have less ability to heal, are at increased risk.

How do you tell if you have an incisional hernia?

The most typical sign is a soft lump on the scar where the surgical incision was made. It's especially noticeable when you stand, walk, cough, or exert yourself. It usually retracts when you lie down or press it with your hand. Sometimes, when you press the lump with your hand and cough, you can feel something pushing up from under your finger (the coughing sensation). In the early stages, you may just feel a slight swelling or pulling pain in the area, which becomes more noticeable with more activity or prolonged standing. If the lump grows larger, it may become more uncomfortable and even affect your daily activities. The most important thing to be vigilant about is if the lump suddenly becomes very hard and painful, and you can't push it back. At the same time, you experience abdominal cramps, nausea, and vomiting, or even stop passing gas or bowel movements. This is a very likely sign of incarceration or strangulation. This is an emergency, and you must go to the hospital immediately without delay.

What should I do if I have an incisional hernia?

This depends on the size of the hernia, your symptoms, and your physical condition. Of course, an incisional hernia cannot heal on its own; the defect in the fascia must be repaired externally. For very small incisional hernias (e.g., less than 2 cm), or if your health is so poor that surgery is not possible at the moment, your doctor may recommend a specialized abdominal binder. This binder primarily serves to contain the bulge, alleviate discomfort, and prevent further enlargement, effectively providing external support for a weak point. However, remember that this is only a temporary solution, not a permanent one. Long-term use can also cause discomfort and even chafing. Ultimately, surgical repair is necessary to truly resolve the problem. Currently, there are two main surgical approaches: One is traditional open surgery, where a second incision is made adjacent to the original incision. The surgeon directly locates the defect in the hernial annulus fascia, pushes back the extruded tissue, and then covers the defect with a specialized patch, securing it securely and suturing it like a patch. This patch is made of a safe material and will gradually integrate with your tissue, providing strong support. This open approach offers clear visualization and ease of operation, making it particularly suitable for larger hernias or complex cases with severe abdominal adhesions from previous surgery. Another approach is minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery, in which the doctor makes several small incisions in the abdomen, inserts the laparoscope and instruments, and then works inside the abdomen, placing a patch on the inner abdominal wall to cover the defect. This approach is less invasive, leaves minimal scars, and offers a relatively quick recovery and less postoperative pain. It is particularly suitable for small to medium-sized hernias and patients who are physically able to tolerate minimally invasive surgery. Your doctor will determine which approach you choose based on the size and location of your hernia, your physical condition, previous surgeries, and your preferences. The recovery period after surgery is crucial, and you must strictly follow your doctor's instructions. Generally, you should avoid heavy lifting for several months after surgery, typically no more than 5 kg. You should also avoid coughing excessively (use hand pressure to protect the wound when coughing), maintain bowel movements, avoid straining, and control your weight. These measures protect the newly repaired area, giving it time to heal and strengthen, significantly reducing the risk of recurrence.

Incisional hernia is a not uncommon complication after abdominal surgery that requires serious attention. If you notice a bulge at the incision site, don't take it lightly; see a doctor immediately. Small hernias or those that are temporarily inoperable can be alleviated with a hernia belt, but surgical repair is the only cure. Current surgical techniques, especially the use of patch reinforcement, are quite effective. The key is early detection, early assessment, and selection of an appropriate treatment plan, as well as strict adherence to the doctor's instructions to protect the wound after surgery. This is the only way to maximize the solution and prevent recurrence.

For more information on Innomed®Silicone contact layer, refer to the Previous Articles. If you have customized needs, you are welcome to contact us; You Wholeheartedly. At longterm medical, we transform this data by Innovating and Developing Products that Make Life easier for those who need loving care.

Editor: kiki Jia

English

English عربى

عربى Español

Español русский

русский 中文简体

中文简体